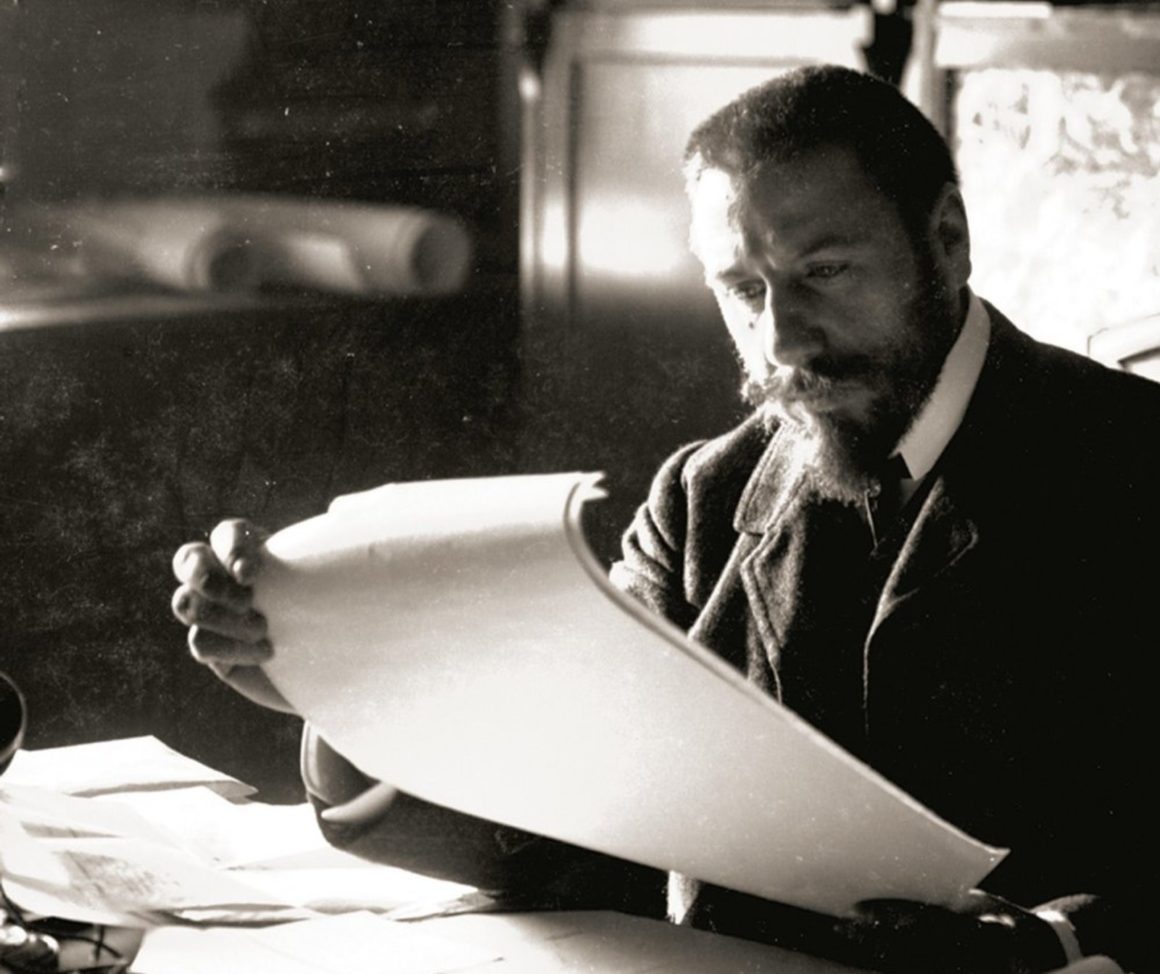

You are no stranger to the first architect on the list with which we start this series. Born and bred on Flemish soil and laying the foundations for the Art Nouveau style through his unique talent, you might have guessed it, we are talking about Victor Horta. With his eccentric designs, which are part of our Belgian street scene, Victor Horta, born in 1861 in Ghent, left a large imprint on the history of not only Belgian but also international architecture. When looking back at his extensive career, experts agree that it can be divided into three distinct phases in terms of style. Would you like to find out more about our fellow countryman? Then you have come to the right place! We, the PureDeluxe team, have listed these phases and then discuss some of his designs.

How it all started for Victor Horta

At a young age Victor Horta decided to leave the Conservatory in Ghent behind and to opt fully for an art course at the Academy of Fine Arts, which he in turn left for a trip to Paris, where he eventually spent three years. Horta and his friend Theo Van Gogh (yes, the brother of Theo) first went to Paris to visit the World Exhibition. One thing led to another and Horta got a job with Jules Debuysson, a French architect and decorator located in Montmartre, which is now very popular with tourists. That Paris and the many people he met there had a great influence on him, he later described in his memoirs with the following quote:

My stay in Paris, my walks and visits to monuments and museums opened all the “doors” of my artistic heart. No school could have taught me more about the enthusiasm for architecture…it stayed with me forever. -Victor Horta

In order to arrive at the final Art Nouveau and Horta style, there was a whole process of impressions and experiences that Horta personally gained through his education, travels and early projects. This process is seen as his first stylistic phase and runs until 1892, after which we are confronted with the second phase of Art Nouveau. The second phase had only just begun when the next, third phase, with slightly less significant projects, was about to begin. This last phase was marked by the two world wars, through which Horta, too, lost his way as a creative genius and finally died in 1947.

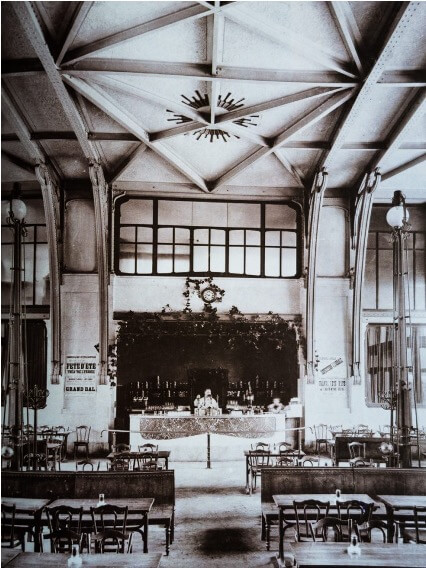

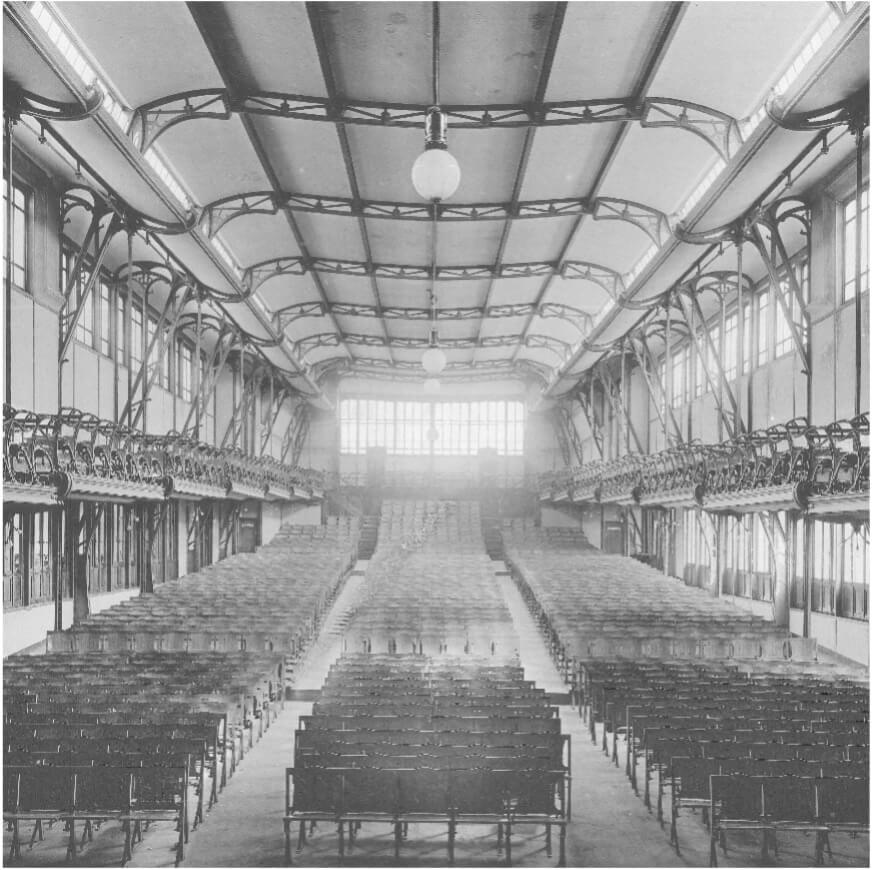

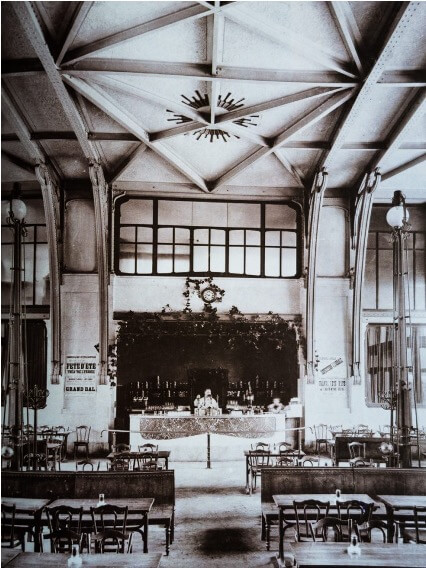

Maison Du Peuple

Rue de la Samaritaine, Brussels

During his years in Paris, Horta met architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. He was one of the many people who inspired Horta. It was specifically Viollet-le-Duc’s theory that interested Horta. This is about reducing nature to geometry, for, according to him, the essence of nature can be represented by a matrix of like-sided triangles. We also speak of triangulation. Horta interpreted the use of geometry as a representation of creativity in nature. The photo below on the left clearly shows the result of Horta’s interpretation. If you look at the ceiling, it consists entirely of a structure of equilateral triangles. The decor pictured belonged to the interior of the café inside Maison Du Peuple, one of Horta’s projects dating from 1896 but unfortunately was demolished in 1965 for a reason that is not entirely clear.

ôtel Autrique

266 Chaussée de Haecht, Brussels

Victor Horta, who always approached architecture as art, goes a step further and considers nature as the basis for a traditional visual language and form. It is here that the personal angle is added through his famous arabesque lines, a clear symbol of originality. The Hôtel Autrique, built in 1894 and still existing in Brussels, was the first place where Horta experimented with his personal aesthetic elements. We are talking about the famous arabesque lines and curved, curly patterns that will appear more and more in his designs from then on. Note especially the white-orange mosaic floor, which was revealed during restoration and contains the famous curly pattern.

Those personal aesthetic elements continued to be present in his life, even when he returned to Belgium in 1880 following the death of his father. Some time later, he started a course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels, where he graduated with high honours. During his training, he worked as a draughtsman for Alphonse Balat, another source of inspiration for Horta and also one of the architects who worked for Leopold II. Both Balat and Viollet-le-Duc inspired Horta with their use of materials that weremodern in their time. For example, we find favoured iron in many of Horta’s designs. Until the 1990s, however, iron was only used for industrial purposes, let alone in homes.

Hôtel Tassel

6 Rue Paul-Émile Janson, Brussels

This house is probably one of Victor Horta’s most famous designs, which is no surprise given its enchantingly beautiful interior, which displays a continuity of arabesque curves and an interplay between constructive and reflective curves. As a result, it is perceived as a single entity, the spatial and decorative unity that Horta was striving for. Émile Tassel, a professor of descriptive geometry, was the one who in 1893 commissioned Horta to design his private dwelling. To do full justice to the graphic design elements, he chose to illuminate the enriched main staircase of the house.

Both outside the building and inside, we see metal and iron constructions that come precisely to life, but above all bear witness to the outstanding craftsmanship of the Belgian ironworkers. Then there is the greenhouse, which contains yellow and white transparent windows framed by iron again. In order to lighten up the room completely, Horta came up with the idea of placing mirrors on the other side of the room. Further on in the house, one last very recognisable element of Art Nouveau is the refined, coloured and curly patterned glass windows. It is this house that put Victor Horta and Art Nouveau on the map during the 19th century.

Horticultural Museum

23-25 Rue Américaine, Brussels

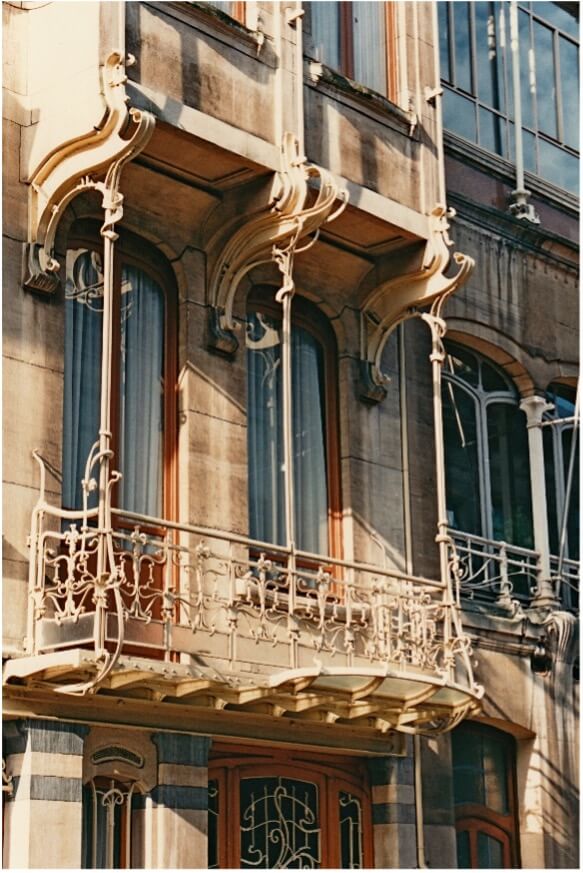

We definitely recommend a visit to the Horta Museum which, like the other houses already mentioned, is also located in Brussels. Originally, it was not a museum but the house and studio of Victor Horta himself. Today, it is known for its good condition and its well-known elements, but in general the continuity of the lines and the combination of different materials create harmony. His later designs will also be similar and thus focus more on individual details than on the whole. Of course, this does not mean that it is not a sensational Horta design. As soon as you set foot inside, you are struck by the strong character of the house which is again royally decorated with alternating marble and mosaics. The character is also shown on the outside with a great eye for detail. The first photo shows a terrace on the second floor, decorated with many curls.

For more information on visiting the museum, please visit: http://www.hortamuseum.be/

In conclusion, we can state that Art Nouveau can be described as an interaction between intensely figurative materials with complex lines and light. These elements occupy a central place in the reconfiguration of the 19th century rationalist traditions. What Victor Horta encountered in Paris and brought out further in his career in Belgium were these rationalist elements, mainly derived from neoclassicism, which he then combined to create his own formal language with a personal aesthetic. This architectural style which characterised him was then very much appreciated in Brussels artistic circles, and with its emphasis on complexity and originality, he transformed the meaning of the building context into a tactile and emotional experience.

Do you want more architecture and design inspiration? Then take a look at our PureLiving page!